News Story

"Bacterial Dirigibles" Emerge as Next-Generation Disease Fighters

BioE Professor and Chair William Bentley discusses "bacterial dirigibles" with the media at the 241st National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society.

Fischell Department of Bioengineering professor and chair William E. Bentley, who developed the bacteria with his research group at the Biomolecular and Metabolic Engineering Laboratories, reported on the novel biodevices at the 241st National Meeting & Exposition of the American Chemical Society (ACS), held in Anaheim, Ca. in March.

"We're building a platform that could allow bacterial dirigibles to be the next-generation disease fighters," he said. "The concept is unique."

WATCH ONLINE: BioE Professor and Chair William Bentley presents the "bacterial dirigibles" concept and answers questions at an ACS Live press briefing.

Bentley explained that in the pharmaceutical industry, traditional genetic engineering is used to reprogram bacteria so that they produce antibiotics, insulin, and other medicines and materials. The bacteria grow in nutrient solutions in enormous stainless steel vats in factories. They release antibiotics or insulin into the vats, and technicians harvest the medicine for processing and eventual use in people.

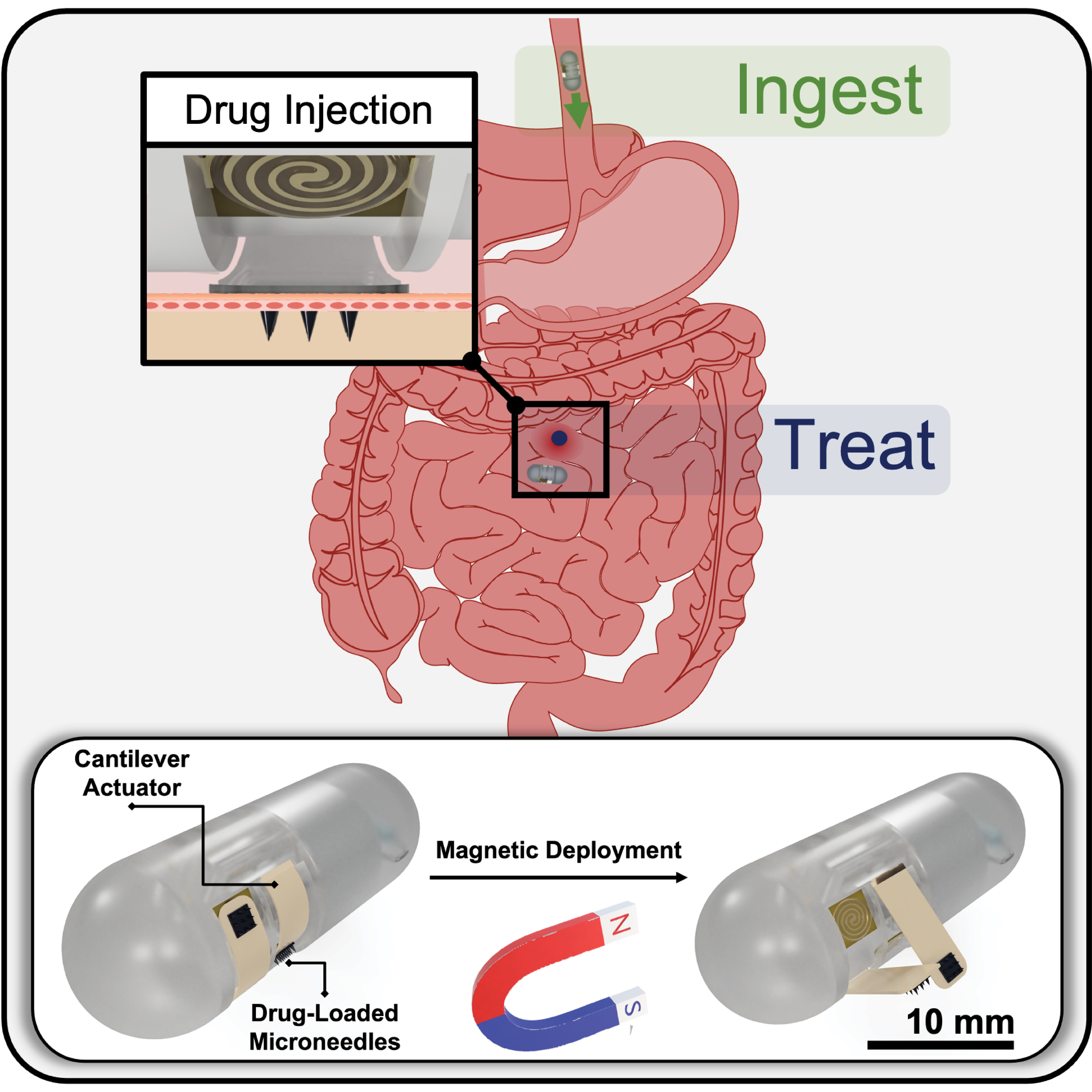

Bacterial dirigibles take the process a step further. Scientists genetically modify bacteria to produce a medicine or another therapeutic substance. Then, however, they give the bacteria a biochemical delivery address, the location of the disease. Swallowed or injected into the body, the bacteria travel to their target, where they start producing substances to fight the disease.

Bentley chose the term "bacterial dirigibles" because the modified bacteria are shaped like blimps or zeppelins, and seem to float like them as they make deliveries. The prototype bacterial dirigible is a strain of E. coli that Bentley and his colleagues modified in the lab.

"We have created a genetic circuit that endows E. coli with targeting, sensing and switching capabilities," he explained. "The resultant cell...autonomously navigates and carries or deploys important 'cargo.'"

The "targeting" molecule is attached to the outer surface of the bacteria. It gives them the ability to "hone in" on specific cells and attach to them—in this instance, the intestinal cells where other strains of E. coli cause food poisoning. Inside the bacteria is a gene segment that acts as a "nanofactory." It uses the bacteria's natural cellular machinery to make drugs, such as those that can fight infections, viruses, and cancer.

The nanofactory can also produce signaling molecules that enable the dirigible to communicate with natural bacteria at the site of an illness. Some bacteria engage in a biochemical chit-chat, called "quorum sensing," in which they coordinate the activities needed to establish an infection. The dirigibles could produce their own signaling molecules that disrupt quorum sensing, preventing bacteria from starting an infection, before it ever requires antibiotics to stop it.

Bentley's group showed that the prototype re-engineered strain of E. coli could both seek out and attach to intestinal cells growing in laboratory cultures, as well as produce chemical signals that triggered neighboring bacteria to make certain proteins that they don't normally produce.

The latter finding means the dirigibles can become enablers that prompt the body to help itself by causing cells to synthesize natural disease-fighting substances, such as immunoglobulins. Immunoglobulins are proteins used by the immune system to identify and destroy foreign invaders, including viruses and the bacteria that cause food poisoning.

Bacterial dirigibles could be given to patients in the form of probiotics, live, beneficial microorganisms like those found in certain kinds of yogurt, Bentley said. Doctors could also inject dirigibles into the bloodstream or directly into a diseased area, such as a tumor.

The bacterial dirigibles research is funded by the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (part of the U.S. Department of Defense), the National Science Foundation, and the Robert W. Deutsch Foundation.

Story adapted from the original press release by and courtesy of the American Chemical Society. Read the original release »

For More Information:

Read "Making Bacteria into Drug Blimps," an article about the research published on MIT's Technology Review web site.

Visit the Biomolecular and Metabolic Engineering Laboratories web site »

Published April 5, 2011